The Darkling Plain

[An Explication of Matthew Arnold’s "Dover Beach"]

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand;

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanched land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Ægean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

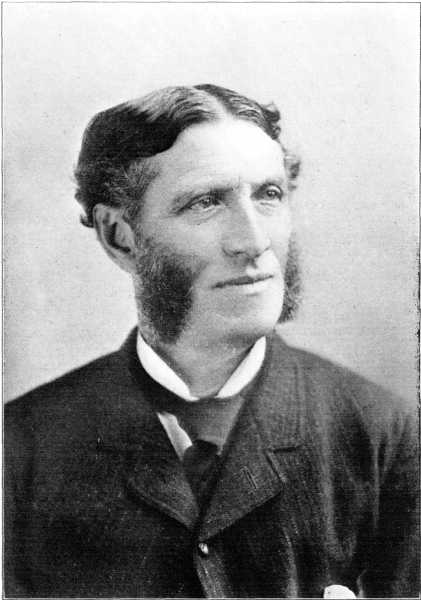

During his honeymoon in 1851, Matthew Arnold visited Dover, England. As he strolled along the beach with his wife, he probably paused to listen to the roar of the English Channel, its waves driven wildly against the shore, or to stare up at the vast white chalk cliffs dominating the coastline. This visit would later serve as inspiration for his poem “Dover Beach.” The poem describes a man’s personal loss of faith, exemplifying the contrast between a time when religion was embraced without question and the modern Victorian age that introduced doubt and atheism.

Arnold believed that his poems would eventually “have their day” because they represented “the main movement of mind” of the Victorian world. Although certainly one of the reasons why he gained prominence, Arnold was also a masterful poet, able to create striking pictures with words. “Dover Beach” begins with such a picture of the calm sea, “the tide is full, the moon lies fair / upon the straits” and “the cliffs of England stand, / Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay” (“Dover Beach”, 2-5). It is not only a picture of Dover, however, but of the whole of England. The British Empire had its height in the Victorian age. England, glorious and powerful, dominated much of the world. Yet in this peaceful scene, suddenly, a “grating roar” is heard “of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling, / at their return, up the high strand” (10-11). The tranquility of the night has been disturbed by this wild noise: the pebbles symbolize new opinions (for instance, Darwin’s theories on evolution) that are flooding the philosophical spectrum and undermining the Christian worldview. Arnold does not question their veracity, but he admits that they bring “the eternal note of sadness in” (14).

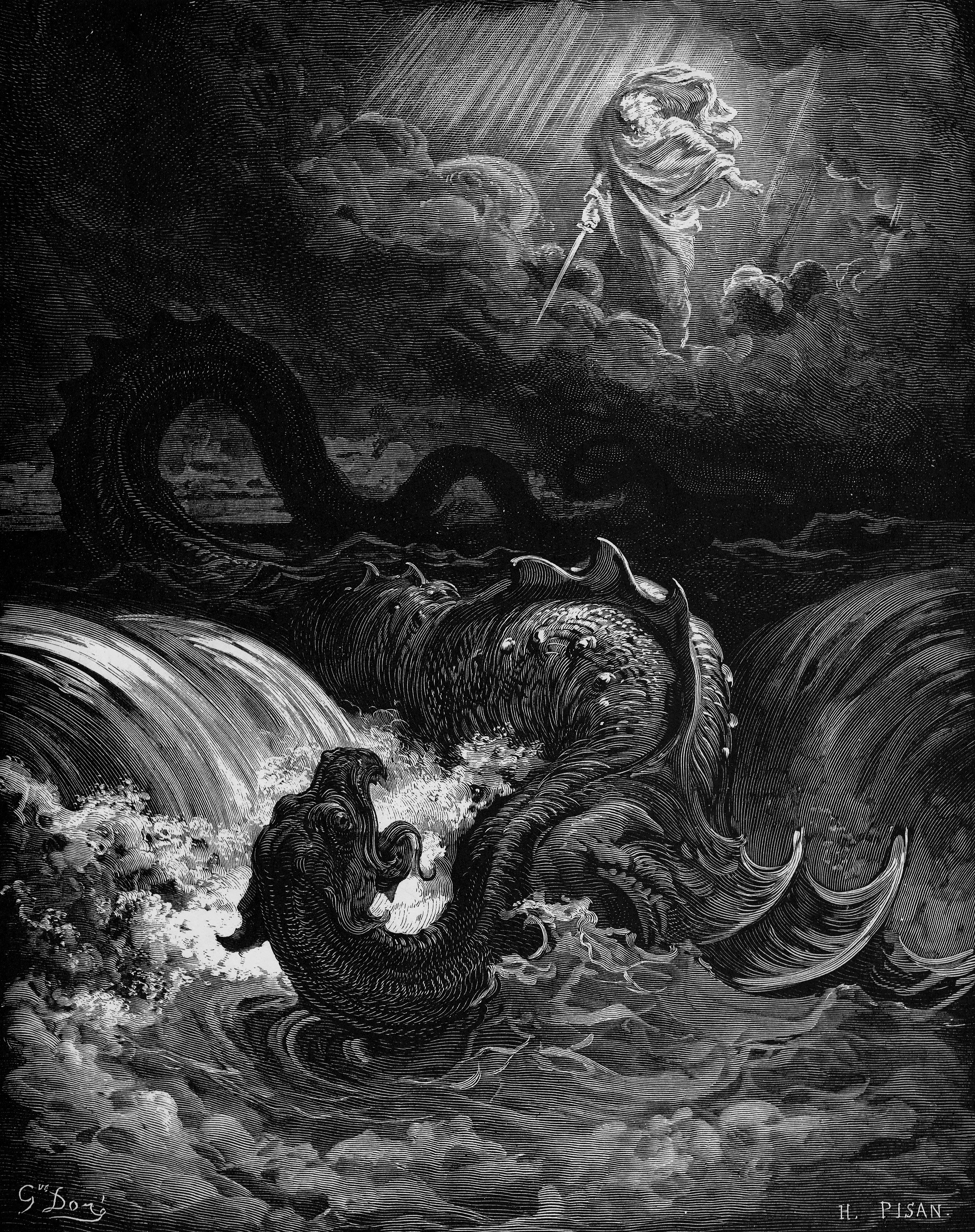

This sound is not new to England, however. Arnold describes Sophocles also hearing it long ago on the Ægean, referring to a passage from Antigone. It is the sound of “human misery” (18), the constant war of differing thoughts and opinions that occurs in any age, country, or culture. Arnold believes nature can be used to discover truths about the world and the sea gives him, like Sophocles, a “thought” (19) that tries to solve this war in his mind. Yet it can hardly offer him a solution. Instead, it reminds Arnold of religion and he compares the real sea to “The Sea of Faith” (21).

This Sea, unlike the sea of nature, can offer man satisfaction for the turmoil in his soul. Indeed, once “at the full, and round earth’s shore” it “lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl’d” (22-23). It is unclear here whether Arnold is referring to a time period (such as the medieval age) or simply to a previous time in his life when Christianity was accepted with absolute conviction and no uncertainty. Whichever the case, when it was accepted, his life did not experience such dark sadness and fear. As he watches his religious beliefs shattered by the new beliefs of the day (beliefs that question the existence of God and the origins of man), he can only hear The Sea of Faith’s “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar, / Retreating, to the breath / Of the night-wind” (25-27). Without Christianity, the world is left naked and forbidding.

Arnold argues, however, that The Sea of Faith was actually a delusion. In reality, the world has “really neither joy, nor love, nor light, / nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain” (32-33). Because Christianity offered these things to Arnold, it must have been false. Arnold has become a nihilist. According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, nihilism is a viewpoint that “traditional values and beliefs are unfounded and that existence is senseless and useless,” denying “any objective ground of truth and especially of moral truths.” He has no way to decide between the warring philosophies because there is no ultimate standard to judge them against. Searching wildly for a solution to this dilemma, Arnold insists on crying out to his “love” (though in the next breath he denounces any love in the world), declaring, “let us be true / to one another!” (29-30). But how can they be true when there is no truth in the world? How can they love one another when love is only a delusion?

No answer is found for these questions. He ends the poem on a note of sorrow, unable to resolve the turmoil in his soul. Instead, he describes himself as on a “darkling plain / Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight, / Where ignorant armies clash by night” (35-37). For the nihilist, the world is in a constant state of war. Fear and despair are its only realities. Arnold seeks desperately to find a shred of happiness that is not a fantasy, but this fights against his own philosophy. Vainly, he attempts to create a substitution for the relationship between God and man, appealing to his fellow man for help. “Let us be true!” he begs, but they have nothing to guide them, no foundation on which to protect such a relationship – the world is hostile, religion is dead, and nature can give them no answers.

Arnold refused to call himself an atheist, hiding in the supposed comforts of agnosticism, refusing to believe in either the existence or the nonexistence of God. Yet, he rejected religion as superficial, blinding to true reality. “Dover Beach” may, in fact, be his only writing that conceded religion was an answer to chaos in the world: it was deceptive, but it did offer relief and a feigned security. However, Arnold insisted on freeing himself from this self-delusion and wallowing in the despair and darkness of the real world. Nevertheless, the Bible is clear that Arnold has actually thrown away reality for the self-delusion. In Romans, Paul wrote that sinful men “suppress the truth in unrighteousness” (Romans, I.18). Further, “they [become] futile in their speculations, and their foolish hearts [are] darkened. Professing to be wise, they [become] fools” (I.21-22). Arnold believed a world of happiness and peace must be a delusion and embraced what he thought was a reality of misery and horror. Indeed, to the unbeliever it is their reality – a “darkling plain” where fools will fight to reject God and hide from the light and truth.

Arnold refused to call himself an atheist, hiding in the supposed comforts of agnosticism, refusing to believe in either the existence or the nonexistence of God. Yet, he rejected religion as superficial, blinding to true reality. “Dover Beach” may, in fact, be his only writing that conceded religion was an answer to chaos in the world: it was deceptive, but it did offer relief and a feigned security. However, Arnold insisted on freeing himself from this self-delusion and wallowing in the despair and darkness of the real world. Nevertheless, the Bible is clear that Arnold has actually thrown away reality for the self-delusion. In Romans, Paul wrote that sinful men “suppress the truth in unrighteousness” (Romans, I.18). Further, “they [become] futile in their speculations, and their foolish hearts [are] darkened. Professing to be wise, they [become] fools” (I.21-22). Arnold believed a world of happiness and peace must be a delusion and embraced what he thought was a reality of misery and horror. Indeed, to the unbeliever it is their reality – a “darkling plain” where fools will fight to reject God and hide from the light and truth.Labels: bookish musings, explication de texte, poetry

Posted by Nicole Bianchi at 8:39 PM

|

![]()

I stumbled over this blog several days ago, picked it up, dusted it off, and was quite displeased to find it so neglected. I hope, therefore, to restore it to the land of the living. My personal musings will still be kept on my xanga blog, but I hope to reserve my more literary reviews and chatter for this journal. I'm not sure if I'll publicize this blog at all, but I always do love it if a reader or two drops by and enjoys.

I stumbled over this blog several days ago, picked it up, dusted it off, and was quite displeased to find it so neglected. I hope, therefore, to restore it to the land of the living. My personal musings will still be kept on my xanga blog, but I hope to reserve my more literary reviews and chatter for this journal. I'm not sure if I'll publicize this blog at all, but I always do love it if a reader or two drops by and enjoys.

This is life seen through the eyes of a writer. A blog that critically examines literature, music, and film. NB, initials which coincidently coinside with the Latin words "nota bene" (mark well), belong to the blog poster, a bibliophile who likes to haunt libraries and book stores, talk about all things bookish, and ramble at any length on things regarding literature. Many of the articles posted here were written as essays for high school and college.

This is life seen through the eyes of a writer. A blog that critically examines literature, music, and film. NB, initials which coincidently coinside with the Latin words "nota bene" (mark well), belong to the blog poster, a bibliophile who likes to haunt libraries and book stores, talk about all things bookish, and ramble at any length on things regarding literature. Many of the articles posted here were written as essays for high school and college.